Introduction¶

The goal of particle physics is to answer fundamental physics questions, such as “Does the Standard Model Higgs boson exist?”, “What is the production cross-section of top-quark pair production?” or “What is the mass of the Higgs boson? To answer these questions statistical tests are constructed as part of the experimental procedure, which result in probabilistic statements on the theory or the observed data.

The goal of these statements is to allow us to come to a decision whether to accept a new theory as worthy of being true, i.e. that it should become physics text books, or should be listed in the Particle Data Book.

Overview¶

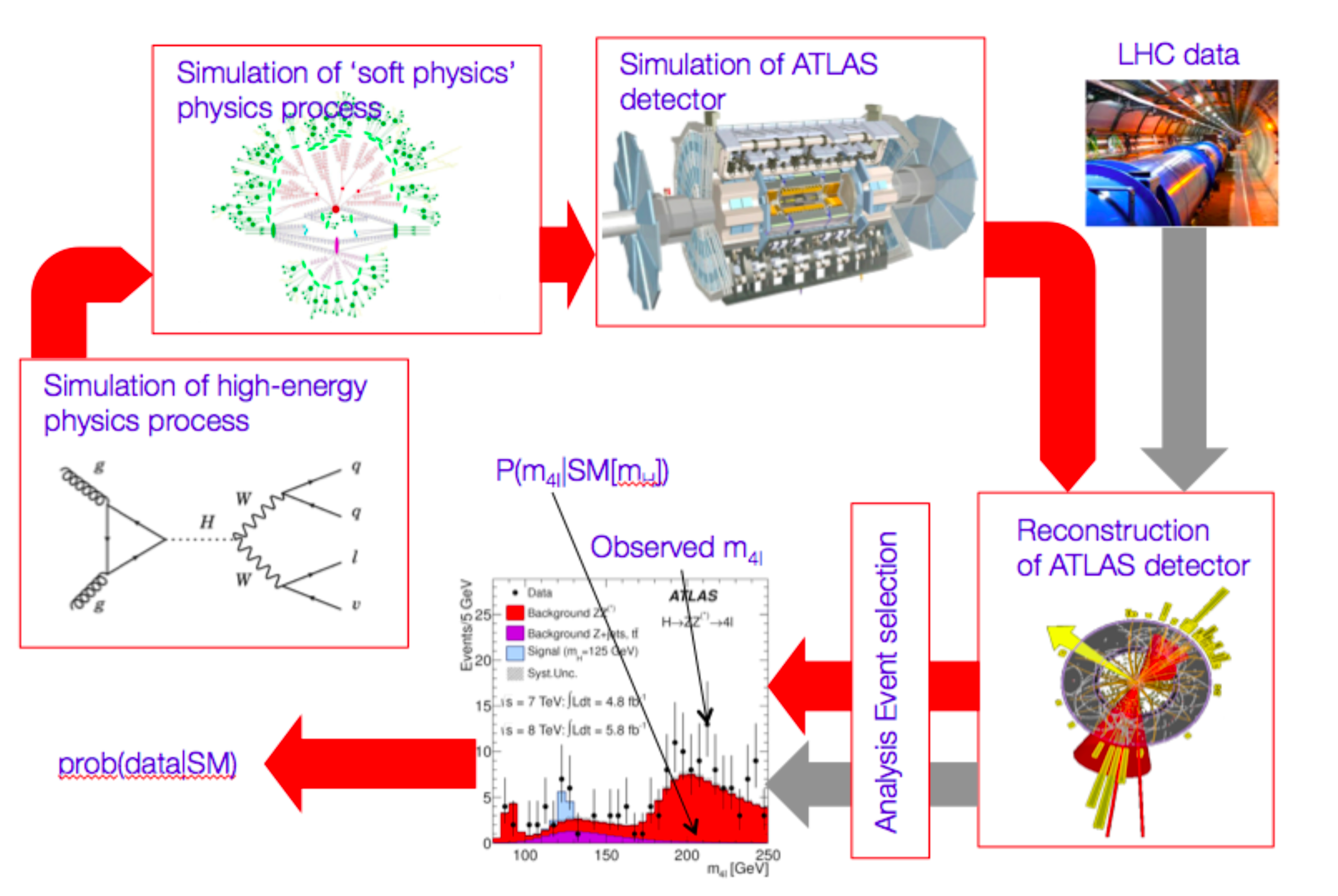

All experimental particle physics results start with the formulation of a physics theory. Examples of such theories are the Standard Model with a Higgs boson, or supersymmetric extensions of the SM. Once a theory of interest is chosen, an experimental measurement procedure is designed that can be used to to test the theory, or to measure one or more parameters of it. In practice this means that we exploit a software chain of physics simulation software, showering Monte Carlo generators, detector simulation software, detector reconstruction and dedicated analysis tools to reduce a preductions of physics theory to a statistical model for one or more effective observables \(\vec{x}\).

A statistical model, or probability model, is mathematical function that assigns a probability \(p\) to every possible observable outcome \(\vec{x}\) of an experiment, under the assumption that a particular hypothesis is true. Once you have such a statistical model of your experiment, all physics knowledge has been abstracted into the model and all further inference on the theory, or its parameters, is purely procedural and uniquely defined given an unambiguous formulation of the type of statement desired [1].

These remaining steps, evaluating the statistical model for the observed data and summarizing the outcome of the evaluation in a convenient form for further interpretation, then result in familiar statements like “The cross-section of squark production is less than 0.3 pb:math:^{-1} at 95% confidence Level”, “The probability to observed this signal, or more extreme, under hypothesis of no Higgs boson is less than \(1.5 \cdot 10^{-8}\), or “The top quark mass has been measured to be \(172 \pm 0.9\) GeV”.

In this document several practical aspects of the building of statistical models, as well as the most commonly used statistical inference procedures based on these models are discussed, starting with very simply models and gradually increasing the complexity to include the level of detail found in modern particle physics analyses.

| [1] | At this point, given the probability model and well defined statement on the type of inference desired, you could pass the remaining calculations to a friendly statistician, or more realistically a software package, that has no physics knowledge. |